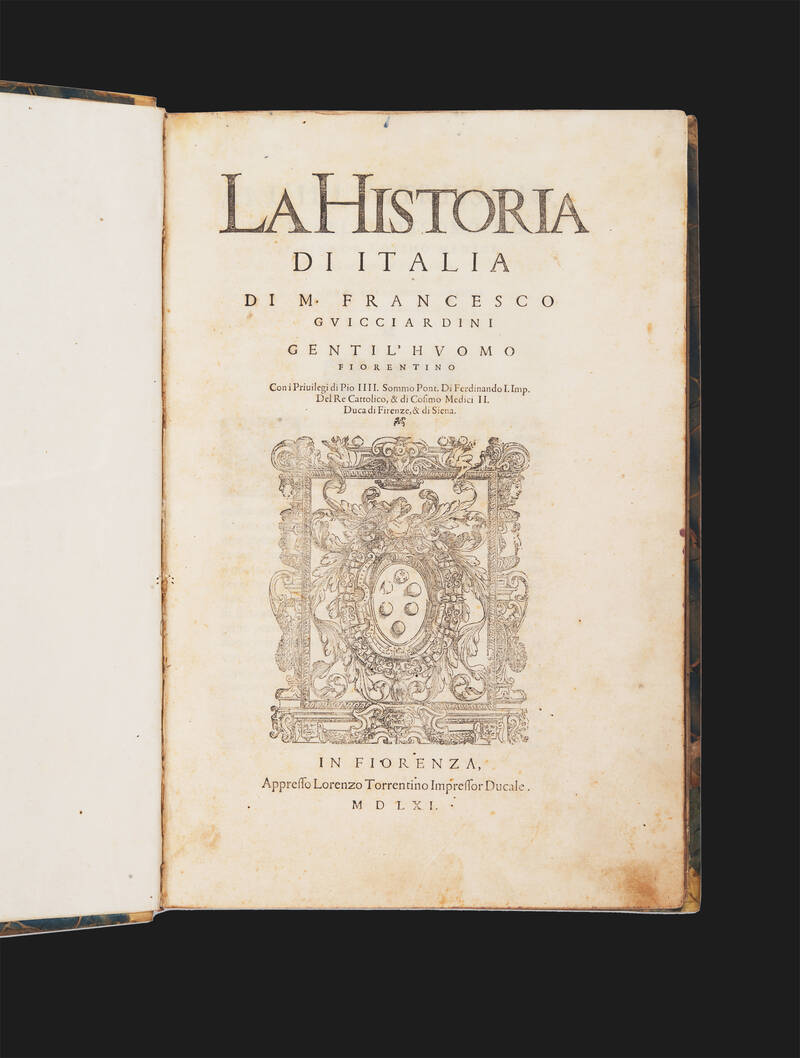

GUICCIARDINI, Francesco. La Historia d’Italia.

Florence, appresso Lorenzo Torrentino Impressor Ducale., 1561.Folio (406 x 265mm.), [8], 665, [2] pages, woodcut printer's device on tile-page and on last leaf, Guicciardini's portrait on πA⁴ verso. Early XIX century half vellum, spine gilt with two morocco lettering-pieces. Light worming, some leaves browned, a few spots, overall a good copy with contemporary manuscript annotations.

Very rare first edition of the ‘first modern history of Europe'(PMM); Francesco Guicciardini magnum opus, the historical account of political events in Italy between 1490 and 1534. Published posthumously by Guicciardini's nephew, Agnolo, the first sixteen books are present in this early edition, the last four being unfinished at the time of Francesco's death, and only later published separately in 1564. According to Graesse, this edition contains three passages - in books 3, 4, and 10 – which were suppressed in later editions. The work is dedicated to Cosimo I de Medici, bearing the Medici coat of arms on the title page.

Guicciardini (1483-1540) was a politician, diplomat to Spain, as well as advisor to Pope Clement VII and Alessandro de' Medici, but most illustrious might be his legacy as historian. “Guicciardini was incorruptible. He was almost fanatically concerned about his honour, which, as he once wrote, is a ‘burning stimulus' to action. But he was a man of strong ambitions, and he was very conscious of his great gifts and talents” (Gilbert). A member of the Florentine elite, Guicciardini was a friend of Machiavelli, with whom he maintained an active correspondence until the latter's death. La historia di Italia reflects this exclusive environment, in which all light is focused on the leaders of states and governments, interweaved with Francesco's analysis of the political dynamics. He is still celebrated as having developed analytical historiographical methods through this work, by describing the politics of the Italian states of the Renaissance with the meticulousness of a detached observer and the insight of an insider analyst.

‘In 1538 when Francesco Guicciardini was fifty-five years old, he began to write a history of the preceding forty years. In the course of his lifetime he had written family memoirs and autobiographical notes, he had composed commentaries on works of others – for example, one on Machiavelli's Discourses – he had outline plans for an ideal constitution of Florence, and twice he had undertaken to write a history of Florence. But the Historia d' Italia stands apart from all his writings because it was the one work which he wrote not for himself, but for the public. When Guicciardini embarked on this last and largest of al his literary enterprises his political career had ended. He was aware that what was for him the greatest fame which man can attain – the fame as a moulder of the political world – had evaded him. But he still yearned for immortality, and he turned to the writing of history because he hoped that literary work might bring him the fame which had escaped him in politics. […] Guicciardini wanted to produce a ‘'true history'' in the humanist sense and this aim is evident on every page of the Historia d' Italia. […] Guicciardini intensified this sordid picture of his own times by alluding to the existence of better times. A brief account of the effects of the discovery of America gave him the opportunity to suggest the possibility of a world not tormented ‘by avarice and ambition'. He made a few comparisons between his own time and antiquity, and in these passages he iterated the humanist notion of the unparalleled greatness of the classical world. […] but averred that perfection is possible only at the beginning, and all things human are thereafter inevitably subject to corruption. To the men of the sixteenth-century the proof of this surrounded them: short-sighted people, vicious people, people of petty interests and aims dominated the political life off their time.' (Gilbert) Guicciardini understood that he could not only write about the grand political events that influenced his nation, but that to understand the clockwork that put them into place, one needed to analyse the characters of the players, while also taking into account the intractable Fortuna which could sway to any side.

‘Beautiful edition of one of the best historical works produced by Italian literature, it once had a great value which its reputation makes it still retain in part'. (Brunet II 1803)

USTC 835391; Edit 16 CNCE 22304; Brunet II 1803; Graesse III 177; BMSTC Italian 320; Adams G 1508; Gilbert, Felix. Machiavelli and Guicciardini: Politics and History In Sixteenth-Century Florence. 1965, pp.271-304.